The Shipyard Nike, or, An Artist Among Workers

AGNIESZKA WOŁODŹKO

What is characteristic for artistic practice in the 21st century is its relocation. The artist no longer works in the isolated space of his or her studio, away from society. Quite the contrary, today’s artists work right in the hubbub of the city, in direct contact with the audience, whose members know more or less what the artist is doing. Workshops, picnics, urban games, and, above all, projects aimed at disadvantaged communities have all become a staple of contemporary art practice. Alas, as sociologist Rafał Drozdowski notes, they are usually ephemeral, being but isolated for-camera events, making it impossible to form even a temporary community between the public and the artist/director. It seems that many artists are motivated by a desire to simply create documentation, which will then be posted online, in the “familiar” space of the Internet, to promote the author and their art among as many people as possible.[1] Local community-centered projects are further encouraged by the relative ease of securing grants for them.

It is in this context that I would like to discuss the project Shipyard by the Gdańsk-based artist Iwona Zając. Being of a relational character towards the shipyard workers, it might be compared to the artistic phenomenon that were the 1st and 2nd Biennales of Spatial Forms which took place in Elbląg in 1965 and 1967. But whereas the Elbląg biennials saw only temporary cooperation between artists and industrial workers, resulting in the creation of artworks that were then installed throughout the city, Zając’s project was of a processual nature, characteristic for “new public art.”

As a resident of the famous Gdańsk Shipyard, running a studio there from 2002,[2] Zając witnessed the enterprise’s ups and downs, attempts to privatize it, its gradual decline and the resulting job cuts. Meeting the workers on a daily basis, she decided to start recording her conversations with them, thus embodying a new role of the postmodern artist, one described and analyzed by authors such as Claire Bishop, Mika Hannula, or Hal Foster. The artist of today listens to social narratives in order to lend them the right aesthetic form and make them more easily comprehensible for the general public. What is particularly valuable, according to Hal Foster, is when an artist manages to bring to daylight stories repressed from the collective consciousness, overwhelmed by the dominant narrative, or, to use a colloquial term, secretly “swept under the carpet.”

Iwona Zając conducted her interviews with the workers employed at the “cradle of Solidarity” at what was a special moment for the legendary shipyard: nearly bankrupt, it was being privatized and restructurized, and its infrastructure – now useless – was being dismantled in front of the very workers. In the interviews, the shipwrights speak about their emotional relationship with a place where they have often worked all their adult life, about what motivated them to choose their profession, about a sense of underestimation, of injustice in the face of the yard’s demise.

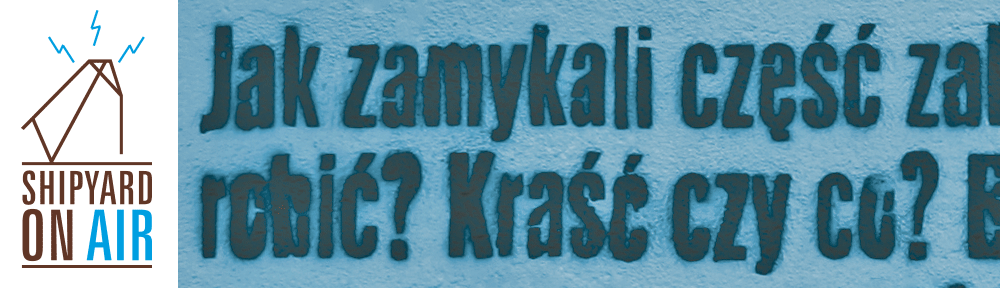

The artist selected the most poignant remarks and, using a stencil, painted them on the wall separating the shipyard from the city. This wall is passed by the workers daily as they walk from the nearby commuter train station to the entry gate. It was also this wall that Lech Wałęsa leaped over, making history, during the 1980 strike. In 2004, courtesy of Zając’s mural, it started speaking in the voices of anonymous workers. Their identification with her work is hardly surprising.

The artist also wrote herself into the polyphony of the shipbuilders’ narratives, considering her presence here as a natural affiliation with the local community. She inserted her own nude image in the central part of the mural, with two shipyard cranes rising from behind her back like wings.[3] The figure was soon christened the “Shipyard Nike.”

It might seem that the mural painting was a finite and complete work. Yet reality itself forced the artist to reopen it when, in late 2012, it was announced that the wall would be demolished due to the construction of a road connecting downtown Gdańsk with the “New City” being developed on post-shipyard sites. This raised the issue of the mural which had already become part of Gdańsk’s urban aesthetics heritage and been branded a “national treasure.” Propositions were made for the part of the wall bearing the painting to be saved and moved elsewhere. Zając didn’t agree to this, preventing her work from backtracking on its original message and sharing the sad fate of the Berlin Wall, dispersed today all over the world and stripped of its original meaning. If the wall was to go, so would the mural, decided the artist. What she wanted to avoid was the dramatic performance of bulldozers pulling down the inscription-covered walls. She spent the cold days of late 2012 painting the mural over with black paint.

The prospect of the work’s imminent destruction prompted Zając to return to the issues raised by it. Thus a dematerializing mural painting turned into a processual, long-term project that reopened themes initiated years before. Above all, however, planning an audio project that would utilize the historical recordings, the artist decided to seek out her interviewees to ask them for permission, as co-authors, to use their voices. Local community-involving artistic projects being so popular today as they are, such a respectful approach was, I dare say, a rare exception. Let it be added, for chronology’s sake, that the audio project in question was presented to the public during the Hydroactive City festival in Gdańsk in June 2013,[4] and then posted online at www.stoczniaweterze.com so that, according to the artist’s intention, the shipyard workers’ voices, broadcast via radio waves, would gain a permanent presence in the city.

Iwona Zając’s shipyard project has been sprouting new rhizomes. By showing works referencing the original mural – embroidered paintings and the film Shipyard Nike Leaving – in the exhibition Telling the Baltic,[5] the artist internationalized a local discourse about Gdańsk’s postindustrial transformation.

Besides the creative process that went into the Shipyard mural, another aspect to consider here is the project’s public reception, which has followed its own logic. The Stocznia workers, as was already mentioned, passing the mural daily on their way to work, came to identify strongly with it. For them, like for a sizeable portion of the Gdańsk public, it had become an inherent part of the urban landscape. News that the wall would be demolished raised instant questions about the future of the mural. But there was more. It seems that the realization that the mural would have to go triggered off a debate about the heritage and future of the shipyard site, prompting questions about where Gdańsk’s urban expansion was heading and doubts regarding the rationale of the “New City”; alternative urbanistic plans were laid out – much too late, however. On January 18, 2013, in the glare of camera flashes, the wall went down, and the painter-over mural with it. Let me leave aside the event’s emotional content. What seems particularly significant for Iwona Zając’s project is the fact that it has engendered, and in a highly expressive and distinct way, a phenomenon of the public sphere, approaching the Habermassian ideal, the presence of which has been heavily doubted by many.